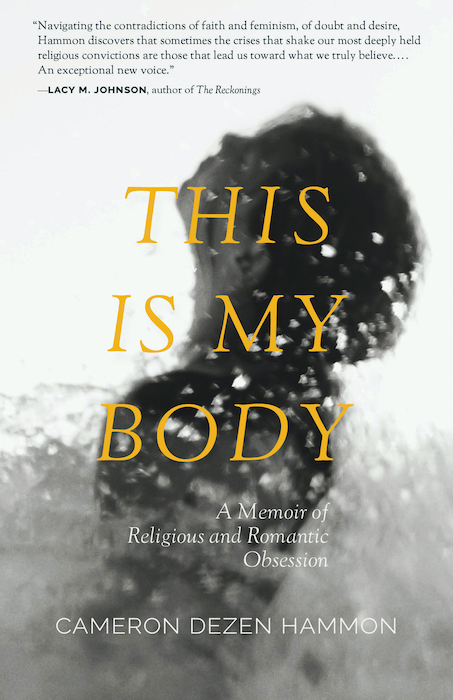

Photo of Cameron Dezen Hammon by Anna Sneed

The story of this interview began in March of 2019 when I heard Cameron Dezen Hammon read a portion of her memoir, This Is My Body, at Powell’s Books in Portland. Something about the patience with which she built the narrative, how deftly she varied details with emotions, and the way she spoke about God and disappointment, made a strong impression on me, as did the intensity of her presence. She was clearly accustomed to being on stage, but written in her gestures was a mixture of command and anxiety: I know what I’m doing here, but I’m not that comfortable telling you this.

This Is My Body upholds the promise of Hammon’s presence I observed that day. The memoir’s sure sentences and careful, critical exploration of becoming an “exvangelical” never quite obscure the tension that grips its author in the process of telling. That’s not to say that the memoir is tense or uncertain, but that Hammon never shirks the seriousness of such truth-telling. I spoke to her about music, privacy, sex and love addiction, and the unquenchable hunger of being alive.

Tell me a little bit about yourself as a writer. It seems like you started out intending to be a musician.

I’ve always gone back and forth between music and writing. I was a vocal major at the High School for the Performing Arts, when I thought I wanted to be on Broadway. Then, when grunge happened, I thought I wanted to be in a band. But then I did an undergraduate creative writing degree at Carnegie Mellon. There I was in a math rock band and writing bad poems, as you do. When I graduated college in 1997, I just wanted to be a rock star, and writing wasn’t even on the horizon. It didn’t even seem like a real thing that one could do. I had a bunch of weird jobs in PR and advertising, and then the religious stuff happened, at the peak of my trying to be a musician, trying to be an artist. I was such a blank slate as far as my identity. In retrospect, I was really looking for a culture or a worldview or a boyfriend or a God that would tell me how to see the world and how to behave in it. Once religion kicked in, music had a place in my life that I could justify. It wasn’t just about me having an ambition or an ego.

All that is to say, I didn’t write prose or poetry or anything other than religious-oriented songs and blogs until 2009, 2010. I started to pull away from the church and the thinking that I had been immersed in and began to remember myself again as a writer. Writing really helped me to rebuild a sense of identity apart from religion.

You released an album in 2016, which is at the time of all the turmoil that This Is My Body is about. It struck me as strange that in the midst of all that, an actual album came out.

[laughs] You are very perceptive. I made that record because I was going insane. I had to do something that wasn’t destructive. I wanted to be able to sing about romantic love in a way that was safe, so I chose to do a covers album rather than write a bunch of songs that people’d wanna know what they’re about. And it worked. It was an incredible time, money, and energy suck—in very good ways. It kept me busy and engaged me creatively, and it gave me somewhere to put all those feelings.

I would’ve lost my mind trying to go through all this and do a record. But it sounds like it was more of an outlet.

Definitely. We started the record in October of 2015, right after I finished my MFA, and we released it in March of ’16. I think I started writing the book that summer. So those months were just so crucial for me. I went right into the next thing that was going to absorb all of my energy and keep me from derailing my life. I guess that’s something I do. It’s some kind of coping mechanism.

But I love that record, and I’m really proud of it. It was quite rebellious for me, I thought, to sing about romantic love. That was a big move, I thought. “Oh, I’m not singing about Jesus, I’m singing about love, and it’s a little scandalous.” I needed that.

I have a question, maybe a tangent, about Christian pop music. My mom once pointed out that Christian music was all major key; it was all uplifting and easy and nice to listen to. I think she was being critical of that worldview, and that’s not really my intent, but I’m fascinated by that being the aim, to have only major key music.

I wonder if your mom said that of Christian music from a particular era, like the eighties and early nineties, because that would be very true. When I was coming into the church, it was the Coldplay years, when every Christian song on the radio followed this formula of a 1-4-5-6 minor (with a 2 minor bridge, this is the Nashville Number System that I’m referring to). So, it’s not major. It’s not that happy-clappy, eighties sound. Because that is real. It’s been years since I listened to Christian radio, but I’m sure we could turn it on right now and find some major key songs from the old days. But when I was coming into it, it was mimicking culture in a way that was almost, almost impossible to discern from the mainstream. I was just in the lobby of a pharmacy, and they were playing Christian radio, and it took me a couple of seconds to distinguish that it wasn’t just pop radio because the lyric was like “You saved me,” and I was like “Oh, here we go. Here we go.” Triggered up and down!

Now, as far as the happy machine? That’s definitely real. And I do think that music plays a part in it. The way that music can manipulate your emotions is one of the most interesting things about the contemporary evangelical church. I was a part of a church when I first moved to Houston that is well-known for its music, and almost everyone that would go there would say, “The first few months I came, I just sat in the balcony and cried.”

Wow.

I would hear this from people from all over the world, and it wasn’t just this church, but other churches in the association of churches—it’s not a denomination, but an association—they would say the same thing. In all these churches, they’re playing the same kind of music, and that music is quite minor key focused. And that’s why it makes people cry. But it’s also this message, “I am unworthy of your love, God, and yet you love me anyway.” And that can really wreck a person. Especially in the key of D minor.

Your memoir makes plain the culture of silence that existed in the churches that you sang for. How did you reconcile silence with singing? It seemed like it was a constant push and pull between the culture of silence and the fact that you had to literally be using your voice the whole time.

Yes. I couldn’t not see the very garish metaphor in the fact that every fucking year, I would lose my voice for months at a time and struggle to do my job. This went on for a decade, if not more. There were times when I wasn’t paid if I wasn’t singing, I couldn’t pay my mortgage. That metaphor, if I were a fiction writer, I wouldn’t use it, because it’s too obvious. Too on the nose.

Rather than silence, I think the culture is even more specifically a culture of prescribed language. You’re expected to say the right words in the right order. As long as you do that, you’re performing belief, fidelity, contentedness, in all of the areas of religious life: marriage, being a mother, work. Everything is within reach of evangelical life. There’s no part of your life that is not included in your faith.

I was silent about the oppression of women, the exclusion and oppression of the LGBTQ community the hypocrisy of leadership, the financial malfeasance—I mean, all of those things were happening, and I was aware of them, but I was using the prescribed script. I was trying to talk about it in my “small group” community, in language that wouldn’t appear to attack but instead was aimed at reforming from within. So many of us—my closest friends were all wrestling with this stuff. But we were doing it in the mother tongue of the church. That in and of itself is a huge problem, of course, because it’s not until you go off-script that you’re really saying the things that need to be said. “Maybe someone who has a vagina could be a teaching pastor.” It’s not until you say that that heads start to roll, and the head that rolls is yours. It’s almost scarier than silence.

You renamed all the churches in the book, and I’m sure you had to not write about some situations to maintain privacy. It seems like it was a big challenge to balance telling the story with that privacy.

It was. The legal responsibilities of publishing a book are so different than when this is just on your laptop. It’s a completely different world. We were many many drafts in with almost nothing changed, and my editor said, “So, these aren’t real names, are they?” and I said, “Um, they are,” and she said, “Ooh, that’s not gonna work.” It was something that I left to the end because I wanted to get the story right, and I didn’t want to be distracted by a fiction I was creating to protect other people.

It’s a lot harder than you think to tell these stories. After #MeToo—and now we have #ChurchToo, which is its own thing—I think the prevailing belief in culture is that it’s really easy to tell these stories. That anyone can write an essay or publish a blog or whatever about their boss when he said something or touched them inappropriately. The truth is that it’s a lot harder than that to get those stories published because the law really does protect people’s reputations. You’re liable if you injure someone’s reputation with accusations, even if they’re true. I would like to see a little bit more of that discussed in the media.

Some of these things happened less than five years ago. Did you consider letting the events of the book settle for longer before you started writing?

No. The book is really about the way that I walked out of restricted evangelicalism and into what’s next, which is something much more complicated and interesting in terms of my spiritual life. As far as the events that took place, depicting the specific events that I depict… I knew that I had to change my life. I had to get out of this dependent cycle on the church. I had to do that in a way that would give me an opportunity to do something other than sing in front of an audience. And the only other thing I can do is write.

There was a lot of heat for me around the events in the book. As they were happening, I was in an emotionally intense space, and I thought it could make interesting prose. I felt like I had to grab that opportunity. I felt a pressure to capture the story as it was happening because I was totally absorbed in and obsessed with it. The only safe way for me to process it was to write about it. I couldn’t quit my job, I didn’t want to destroy my marriage, I didn’t want to turn all that energy onto my life, so I turned it onto the project of writing the book. It bought me a lot of time to process what had happened.

Phillip Lopate said something like the plot of a personal essay is watching a writer struggle with their own psychic defenses. You’re watching a mind at work trying to deal with their own self-protective bullshit and get into what is really going on. I think that can be done with stuff as it’s happening. You are struggling with your psychic defenses in the middle of a crisis. Melissa Febos has talked about this regarding Abandon Me, and it was incredibly inspiring for me when I was writing this book. She wrote her book when she was also in the middle of living that story. So I thought, it can be done, and I’m gonna have to do it.

So you’re writing it as it’s happening. Did you write it in essays? The book is so smooth and flows from one thing to another incredibly easily, but you’re talking about the revision process as if it was very laborious.

Yes. Yes. The smooth book that you have is smooth because it was edited thoroughly and intensely. It was laborious, but not in a negative way. The book was basically the form that it is today as far as the jumping around in time. Some pieces of it began as essays, but those essays were all cut, eventually. For example, there was a whole chapter on my husband’s drinking and how we came to terms with it, and the bayous—it was an essay that I published with the Butter, years ago, and I had shaped it into a chapter. We worked and worked and worked on that chapter, and then finally, I realized it had to go. It was kind of like scaffolding. The essays were scaffolding that started the process, but then eventually, scaffolding always has to come down.

About the addiction aspect. As I was reading about you going to sex and love addicts meetings, I kept thinking about Erica Garza’s memoir, Getting Off. She writes about addiction to porn and masturbation, and she gets completely wrapped up in sexual gratification, to the exclusion of safety and happiness. That doesn’t resemble what you went through. Is there stuff you left out of the book that looked more like a traditional addiction?

Great question. Sex addiction and sex and love addiction are not the same thing. What you’re describing with Garza—that would fall under the SA banner. When you think of sex addiction, you think of compulsion and going to prostitutes, all of the extreme things. Sex and love addiction is a lot quieter. As far as the A fellowships, it’s fairly small and pretty new. What it looks like to the person who ascribes to these ideas is a combination of codependence and romantic love, when codependence characterizes your romantic relationships. It’s kind of subtle, and in fact, most people at some point in their lives can probably identify with what makes a person a “sex and love addict.”

Early on, when I was first going to these meetings, I was going truly to prove that I was not this thing. Then I started to hear people share, and the things they were sharing were very similar to what I was going through.

I was in before I acted out at a level that would be considered egregious, yes. I was in the program to prevent myself from taking it further.

It’s such a safe, preventive move.

This is a big part of my personality: I’m hypervigilant, and I had watched my parents’ marriage disintegrate in a way that I was determined not to allow my own marriage to disintegrate. And it wasn’t so much that I believed I was a sex and love addict, it was that someone gave me a program to follow and I did diligently follow that program.

I was struck by one line in particular: “I begin to worry that my hunger cannot be satisfied by God.” That’s almost the theme of the whole book. You’re hungry, you try God, and God just keeps not being enough over and over. Has that been resolved for you at all?

Has my hunger been satisfied? No. It hasn’t. And I don’t think it will be. I think the idea that it can be satisfied is a fictional idea. But that is the thing that Christians or Protestants will say. It’s a C.S. Lewis idea, that everyone has a God-shaped hole in their heart. Even if it’s not God-shaped, I think a lot of people have that gnawing hunger for something else. For me, I think God did satisfy it for a long time, and that’s why I wrote that line. That moment was the beginning of that changing for me.

Before I considered that God might not be enough, I felt I was at one with my purpose. At the height of my zealous belief, I knew exactly why I was born; I knew exactly what I was meant to do. I felt locked into a track, exactly where I should be. That’s a really intoxicating place. It’s a high.

What’s next for you?

Well, I have written what I hope will eventually be a novel. It may never, ever appear anywhere other than on my hard drive. But I am writing fiction. I’m also writing a treatment of the memoir for a series, and that’s fun because it’s a totally different medium. I’m doing a little book tour. First of the year, I’ll have to face the blinking cursor again and really get back to the writing.

Cameron Dezen Hammon’s debut This Is My Body will be released on October 22, 2019 by Lookout Books.